To help make the European debate decent and civilised, it is now more important than ever to value the skills of the linguist.

I began learning German at the age of 13, and I’m still trying to explain to myself why it was love at first sound. The answer must surely be: the excellence of my teacher. At an English public school not famed for its cultural generosity, Mr King was that rare thing: a kindly and intelligent man who, in the thick of the second world war, determinedly loved the Germany that he knew was still there somewhere.

Rather than join the chorus of anti-German propaganda, he preferred, doggedly, to inspire his little class with the beauty of the language, and of its literature and culture. One day, he used to say, the real Germany will come back. And he was right. Because now it has.

Why was it love at first sound for me? Well, in those days not many language teachers played gramophone records to their class, but Mr King did. They were old and very precious to him and us, and he kept them in brown paper bags in a satchel that he put in his bicycle basket when he rode to school.

What did they contain, these precious records? The voices of classical German actors, reading romantic German poetry. The records were a bit cracked, but that was part of their beauty. In my memory, they remain cracked to this day:

Du bist wie eine Blume – CRACK – So hold und schön und… – CRACK (Heinrich Heine)

Bei Nacht im Dorf der Wächter rief… – CRACK (Eduard Mörike’s Elfenlied)

And I loved them. I learned to imitate, then recite them, crack and all. And I discovered that the language fitted me. It fitted my tongue. It pleased my Nordic ear.

I also loved the idea that these poems and this language that I was learning were mine and no one else’s, because German wasn’t a popular subject and very few of my schoolmates knew a word of it beyond the Achtung! and Hände hoch! that they learned from propaganda war movies.

But thanks to Mr King, I knew better. And when I decided I couldn’t stand my English public school for one more day, it was the German language that provided me with my bolt-hole. The year was 1948. I couldn’t go to Germany, so I went to Switzerland and at 16 enrolled myself at Bern university.

And in Switzerland, instead of Mr King, I had another admirable teacher in Frau Karsten, a stern north German lady with grey hair in a ponytail, and she, like Mr King, rode a bicycle, sitting very upright with her grey hair bobbing along behind her.

So it’s no wonder that when later I went into the army for my national service, I was posted to Austria. Or that after the army I went on to study German at Oxford. And so to Eton, to teach it.

You can have a lot of fun with the German language, as we all know. You can tease it, play with it, send it up. You can invent huge words of your own – but real words all the same, just for the hell of it. Google gave me Donaudamp-fschiffsfahrtsgessellschaftskapitän.

You’ve probably heard the Mark Twain gag: “Some German words are so long they have a perspective.” You can make up crazy adjectives like “my-recently-by-my-parents-thrown- out-of- the-window PlayStation”. And when you’re tired of floundering with nouns and participles strung together in a compound, you can turn for relief to the pristine poems of a Hölderlin, or a Goethe, or a Heine, and remind yourself that the German language can attain heights of simplicity and beauty that make it, for many of us, a language of the gods.

And for all its pretending, the German language loves the simple power of monosyllables.

The decision to learn a foreign language is to me an act of friendship. It is indeed a holding out of the hand. It’s not just a route to negotiation. It’s also to get to know you better, to draw closer to you and your culture, your social manners and your way of thinking. And the decision to teach a foreign language is an act of commitment, generosity and mediation.

It’s a promise to educate – yes – and to equip. But also to awaken; to kindle a flame that you hope will never go out; to guide your pupils towards insights, ideas and revelations that they would never have arrived at without your dedication, patience and skill.

To quote Charlemagne: “To have another language is to possess a second soul.” He might have added that to teach another language is to implant a second soul.

Of course, the very business of reconciling these two souls at any serious level requires considerable mental agility. It compels us to be precise, to confront meaning, to think rationally and creatively and never to be satisfied until we’ve hit the equivalent word, or – which also happens – until we’ve recognised that there isn’t one, so hunt for a phrase or circumlocution that does the job.

No wonder then that the most conscientious editors of my novels are not those for whom English is their first language, but the foreign translators who bring their relentless eye to the tautological phrase or factual inaccuracy – of which there are far too many. My German translator is particularly infuriating.

In the extraordinary period we are living through – may it be short-lived – it’s impossible not to marvel at every contradictory or unintelligible utterance issuing from across the Atlantic. And in marvelling, we come face-to-face with the uses and abuses of language itself.

Clear language – lucid, rational language – to a man at war with both truth and reason, is an existential threat. Clear language to such a man is a direct assault on his obfuscations, contradictions and lies. To him, it is the voice of the enemy. To him, it is fake news. Because he knows, if only intuitively, what we know to our cost: that without clear language, there is no standard of truth.

And that’s what language means to a linguist. Those who teach language, those who cherish its accuracy and meaning and beauty, are the custodians of truth in a dangerous age.

And if they teach German – and teach it in this my beleaguered country – they are quite particularly to be prized, all the more so because they are an endangered species. Every time I hear a British politician utter the fatal words, “Let me be very clear”, these days I reach for my revolver.

By teaching German, by spreading understanding of German culture and life, today’s honorands and their colleagues will be helping to balance the European argument, to make it decent, to keep it civilised.

They will be speaking above all to this country’s most precious asset: its enlightened young, who – Brexit or no Brexit – see Europe as their natural home, Germany as their natural partner, and shared language as their natural bond.

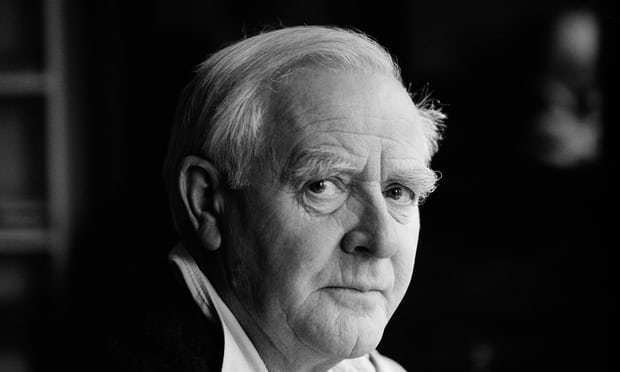

After studying in Switzerland and national service, John le Carré (aka David Cornwell) was posted to the British Embassy in Bonn as a Second Secretary, and then went on to Hamburg as British Consul. This text was originally part of a speech given by le Carré at an award ceremony at the German Embassy for German teachers on 12 June.

Source: The Guardian